Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

People mistakenly think that they have to wait for the weather to start warming up before they can crank up the heat in the gym. That’s great if you want a body that is only seasonally in great shape, but if you want a body that’s rock solid year-round, then plyometric-based training should be a big part of your program.

Plyometrics, which call for muscles to exert a huge amount of force in as little time as possible, consist mostly of jumps and other explosive moves. You may think that plyos should be reserved for competitive athletes, but you’d be wrong. Plyos put a heavy demand on your body’s fast-twitch muscle fibers — those most responsible for explosive movements and power production, and those most prone to curve-inducing growth. And they also can have a huge impact on your productivity in other exercises. One study showed that athletes who performed heavy squats immediately before hitting the track had better sprint times than those who did not, an effect known as potentiation. This effect can be attributed to your body sensing a need to call more muscle fibers into action for what comes next. Not surprisingly, a study in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance found that athletes who did a few plyometric push-ups or medicine-ball chest passes before maxing out on the bench were able to move more weight. If you need another reason to use plyos, consider that the focus on fast-twitch muscle fibers is also likely to yield greater postworkout metabolism than your run-of-the-mill cardio session.

Put simply, plyometrics help your muscles flip the switch to “fierce,” helping you to perform better in the gym and look better as a result. Assuming that you aren’t going to be training for the next Olympics, a routine that combines plyometrics with traditional training helps you get the best of both worlds.

The Plyo Exercises

Jump Squat

Emphasis:quads, glutes

It is as it sounds — a squat with a plyometric component. Using only your bodyweight, descend into a full squat, then explode out of the bottom, swinging your arms upward aggressively to catch as much air as possible. Land softly and immediately descend into your next rep.

Plyometric Incline Push-Up

Emphasis: chest, shoulders, triceps

Set yourself up in push-up position with your arms fully extended, hands placed just outside of shoulder-width apart on the edge of a fixed bench. Bend at your elbows and shoulders to lower down toward the bench. Go as deep as you comfortably can, then forcefully press back up to full extension, your hands leaving the bench for a moment at the top. “Catch” yourself with soft elbows and immediately descend, under control, into your next rep.

Jumping Lunge

Emphasis:glutes, hamstrings, quads

Start by taking one long, deliberate stride forward, like you would in a stationary lunge. With your hands at your sides, descend into a lunge, making sure to keep your front shin and rear thigh perpendicular to the floor. Stop just short of your rear knee touching the ground and then jump up, switching your legs in the air and landing with your other foot forward. Repeat the process, alternating legs on each rep.

Jump Rope

Emphasis: calves

Jumping rope doesn’t fit the “explosive” description as tidily as the previous exercises — it is more ballistic, or bouncy, in nature, but the same quick-touch effort applies. You don’t have to work the rope like a champion prizefighter — simply work the rope into a comfortable rhythm that you can sustain for the prescribed time or revolutions. You can start out on both feet, but ideally, you’ll want to challenge yourself by alternating feet with each turn of the rope to make it more challenging overall and unilateral in nature.

The Workout

This routine, which is really two in one, will take you about 20 minutes, door to door, not counting a thorough warm-up and a few minutes between circuits. Each circuit has a slightly different emphasis.

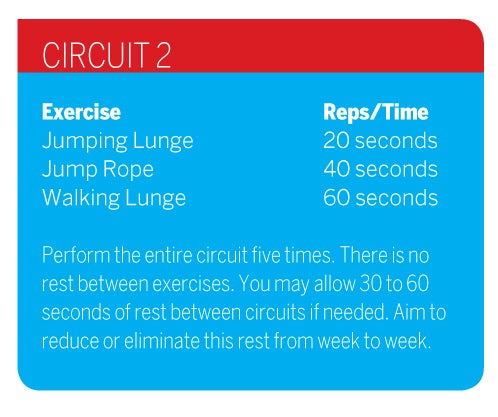

>> Circuit 1. The first circuit is a progressive trek from the highly demanding to the moderately demanding, with the rep totals increasing on each move. It incorporates both lower- and upper-body moves for a head-to-toe thrash that recruits tons of muscle, burns boatloads of calories and may leave you looking for a bucket. But here’s the good news: It’s only 10 minutes. Borrowing a page from the CrossFit universe, you’ll perform as many rounds of this circuit as possible in 10 minutes. Each week, you’ll aim to perform at least one more complete circuit than the week prior but in the same amount of time. And no, partial rounds do not count.

You’ll start off with the most demanding move of the bunch: the jump squat. By doing such a butt-kicking, fast-twitch plyo move first, you fire up your central nervous system to perform at a higher level for everything that follows, including kettlebell swings and standard bodyweight squats. Plyometric incline push-ups are as tough as it gets for upper-body explosiveness and are therefore also done early in the circuit. Traditional incline push-ups come later and allow you to dig into your remaining chest and shoulder muscle fibers.

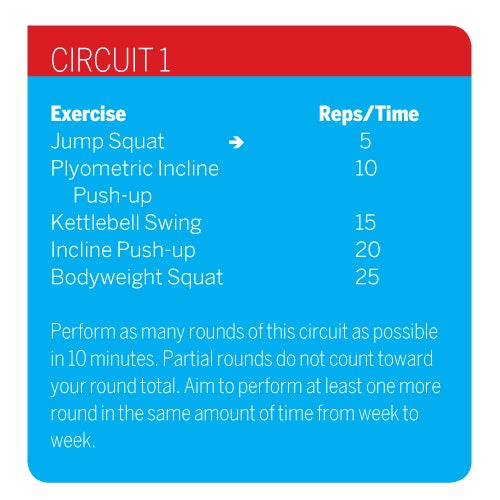

>> Circuit 2: After a one- to two-minute rest, you’ll be back at it with another challenging circuit, only this one will be based on time, not total reps. Again, the most demanding move — the jumping lunge — is done first in this lower-body-focused battery of exercises. You’ll follow it with some time on the jump rope, which bridges the gap between the use of your explosive energy stores and your more customary fuel (glycogen, or stored sugar), which is the primary source during lunges